Reflections on One-Forty’s Migrant for Migrant Workshop: Balancing Money, Identity, and Ideals

Attending the latest One-Forty workshop left me reflecting on how identity, economics, and community shape the migrant experience. As I set aside my PhD applications for the day, I thought I’d write down my thoughts on the event and the questions it evoked in me.

Setting the Scene

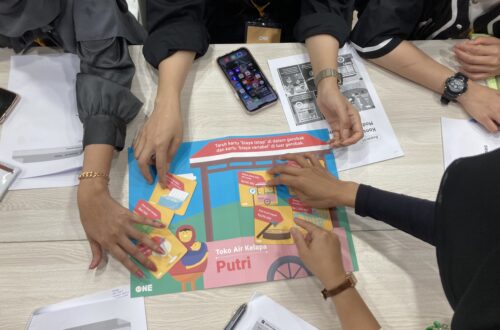

The “Migrant for Migrant” (M4M) program is a new initiative by One-Forty aimed at empowering migrant leaders and giving them space to organize their own activities. Yesterday’s workshop, led by an Indonesian migrant entrepreneur, drew forty women who were eager to learn more about running small businesses. The event was infused with a strong sense of Indonesian culture: Islamic greetings, a pantun (rhyming poem), prayer time, and a series of opening speeches full of gratitude. It felt like a miniature version of the official events I’ve attended back home.

One moment that stood out was the slogan the organizers taught us: “If I say ‘PMI’ [Indonesian migrant workers], you say ‘We refuse to go home without dollars!’” The slogan’s humorous undertone was met with laughter and camaraderie. Yet, within the room, this call seemed to resonate deeply. For many, working in Taiwan is primarily about financial opportunity—one that’s harder to find at home. Skill-building, as I gathered, wasn’t framed as a personal development journey but as a means to a practical end: economic security.

Money as Motivation

The slogan brought up conversations I’ve had with other migrant workers. Many left Indonesia not because there were no jobs but because local salaries don’t compare to the earnings potential abroad. This drive to “not go home without dollars” is a testament to their determination—but also, it raises questions for me. Should learning be so transactional? Or am I imposing my own ideals here, expecting some “higher” purpose behind their motivation to learn?

Gender and Identity

A transitional justice practitioner from another NGO attending the workshop, shared an interesting observation with me. During an icebreaker, each group was asked to introduce two things they all had in common. Many said, “We are all migrant workers and we are all women.” Two spokespersons added, with a laugh, “And because we are women, we all like cooking, travelling, and, most importantly, taking selfies—which is basically what travelling is for!”

The humour was lighthearted, yet these statements also highlighted an intersection of gender and identity in the room. This brief interaction showed how gendered expectations around interests and aspirations influence both group dynamics and personal expression. In celebrating these shared identities, the participants created a unique space of belonging—one that shaped not only how they connected with each other but also how they saw themselves.

From A’s rights-based perspective, however, such statements, like “men/women like this because we are men/women,” should be addressed, as they can reinforce restrictive gender norms that might be considered “violent” in their impact on self-identity and rights.

Sustainability in Small Business

The presenter encouraged participants to consider using fake flowers in their bouquets for practical reasons—they’re durable and available on short notice. It’s sound advice from a business perspective. But as I looked around the room at the discarded plastic stems and wrappers, I couldn’t help feeling uneasy about the waste generated. The plastic flowers may be cost-effective, but at what environmental cost?

Maybe I’m on a moral high horse, but these kinds of moments make me pause. Is it fair to hope for sustainability ideals in communities where economic and social security take precedence?

Larger Questions and Contradictions

All of this left me with questions that I’m still mulling over. Economic opportunities abroad give many migrants a taste of the lifestyles seen in Indonesian cities. Some scholars write about “consumptive behaviours” of returning migrants, but urban Indonesians are equally consumer-driven; they just have stable salaries to support it. And so, for migrants, is the root problem really a lack of jobs? Or is it an underlying capitalist mindset, one that we share and rarely examine?

If we’re working toward sustainable development, how do we balance this drive for financial stability with ideals of environmental consciousness, gender equality, and religious tolerance? It’s a contradiction I wrestle with, and perhaps my own values are more influenced by “elite ideals” than I realised.

Closing Thought

In a world where economic survival is often the primary goal, should we continue to hope for deeper, collective changes in mindsets around sustainability and inclusivity? Or is this expectation unrealistic in communities simply trying to make ends meet?

Discover more from Elhana S.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hey guys, just wanna ask something.Is Win Adda Safe to play online for real cash? Any reviews? Do let me if know if it’s the deal to go it. Link iswinaddasafe

Spinwin777, my man! Found some serious luck here last night. Slots were HOT! Check it out if you’re huntin’ for a good time and maybe some extra cash! spinwin777

Alright alright alright, 666game, not gonna lie, it’s pretty addictive. Got a decent selection and it runs smooth on my phone. Give it a shot if you’re bored! 666game