Did you know that among Taiwan’s 23 million people, over 760,000 are migrant workers employed in low-skill, low-paying industries like domestic care and factory work? This means that 1 in 33 people in Taiwan is a migrant worker, most of whom come from Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand.

Migrant workers in Taiwan

- Vietnam: 256,576

- Indonesia: 255,874

- Philippines:154,027

- Thailand: 67,954

Taiwan employs a “guest worker” system, a prevalent labour migration model in many Asian countries. Under this regime, migrant workers are hired on temporary contracts and are not allowed to immigrate or become naturalized citizens. This approach is common in countries that lack a history of immigration or an ideology favouring permanent settlement (Massey et al., 1998).

The Visibility of Migrant Workers in Taipei

During the Moon Festival holiday in Taipei, I met an American who used to live in Hong Kong. Our conversation about the guest worker system led him to observe that, unlike in Hong Kong—where migrant workers gather openly at Victoria Park on Sundays—he hadn’t seen as many migrant workers in Taipei. However, while less visible, many migrants gather inside Taipei Main Station on Sundays, making their presence less noticeable to locals.

Outside of Sundays, most migrants work in places where they remain unseen by the public—cooking, cleaning, changing adult diapers, assembling parts on production lines, building the MRT, or sailing on fishing vessels. While I had always known this, seeing these workers’ photographs gave me a fresh perspective. That’s the impact of Voice of Migrants.

What is Voice of Migrants?

Voice of Migrants (VOM) is a long-standing photography project by One-Forty. The initiative uses powerful images to “spark hope and inspire action” among migrant workers and the wider community. The project is rooted in Photovoice theory, pioneered by Professor Caroline Wang of the University of Michigan. One-Forty has adapted this into a community-based participatory photography training program for migrant workers across Taiwan, holding workshops, photo contests, and exhibitions. The VOM website showcases hundreds of photographs taken by migrant workers, accompanied by the real stories behind them.

Photovoice is a visual research methodology that puts cameras into the participants’ hands to help them to document, reflect upon, and communicate issues of concern, while stimulating social change. (Budig, Diez, Conde et al., 2018)

Last Sunday, I attended the annual photo competition ceremony at One-Forty’s office. Thirty photographs were displayed on the wall, stories written underneath in Indonesian, Thai, Tagalog, Vietnamese, English. I remember standing there, holding up my phone, scanning the descriptions with Google Translate, trying to make sense of it all. But even without the words, the images said it all.

Stories Behind the Photos

One-Forty has received 7,506 photos and stories from Southeast Asian migrant workers. These include personal reflections on their experiences in Taiwan.

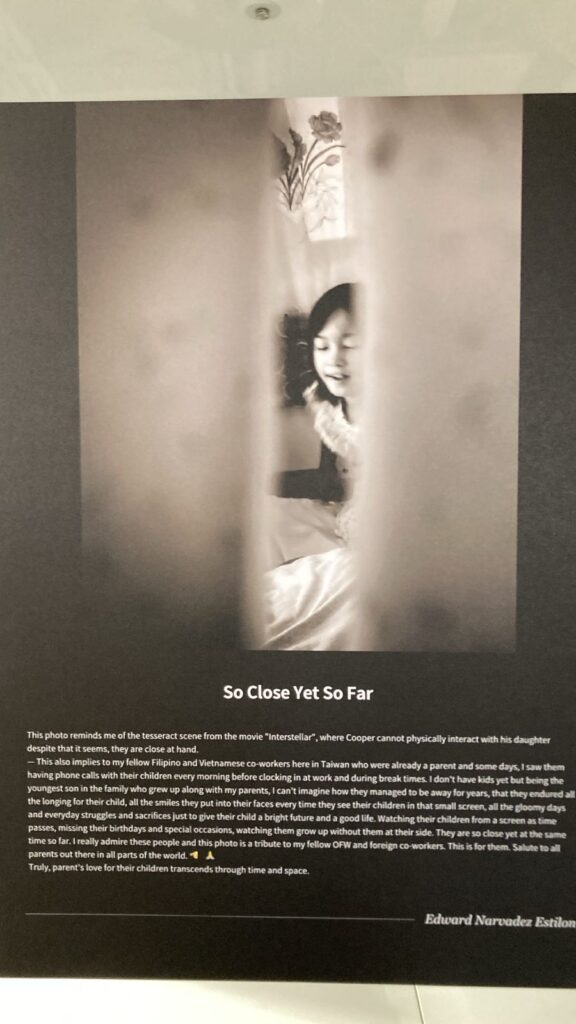

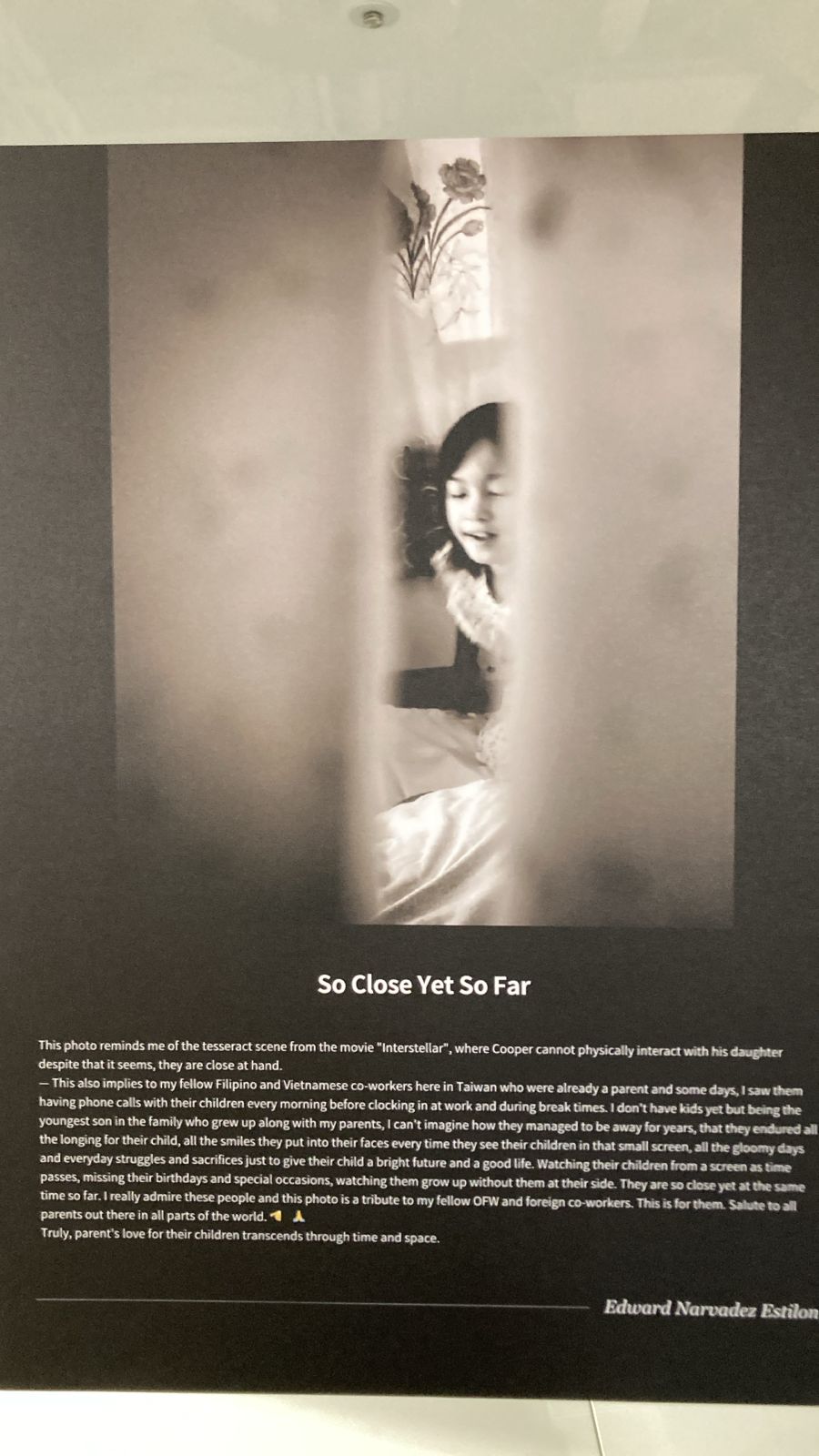

For example, the picture above from Edward Narvadez Estilon says:

This photo reminds me of the tesseract scene from the movie “Interstellar”, where Cooper cannot physically interact with his daughter despite that it seems, they are close at hand. This also implies to my fellow Filippino and Vietnamese co-workers here in Taiwan who were already a parent and some days, I saw them having phone calls with their children every morning before clocking in at work and during break times. I don’t have kids yet but being the youngest son in the family who grew up along with my parents, I can’t imagine how they managed to be away for years, that they endured all the longing for their child, all the smiles they put into their faces every time they see their children in that small screen, all the gloomy days and everyday struggles and sacrifices just to give their child a bright future and a good life. Watching their children from a screen as time passes, missing their birthdays and special occasions, watching them grow up without them at their side. They are so close yet at the same time so far. I really admire these people and this photo is a tribute to my fellow OFW and foreign co-workers. This is for them. Salute to all parents out there in all parts of the world. Truly, parent’s love for their children transcends through time and space.

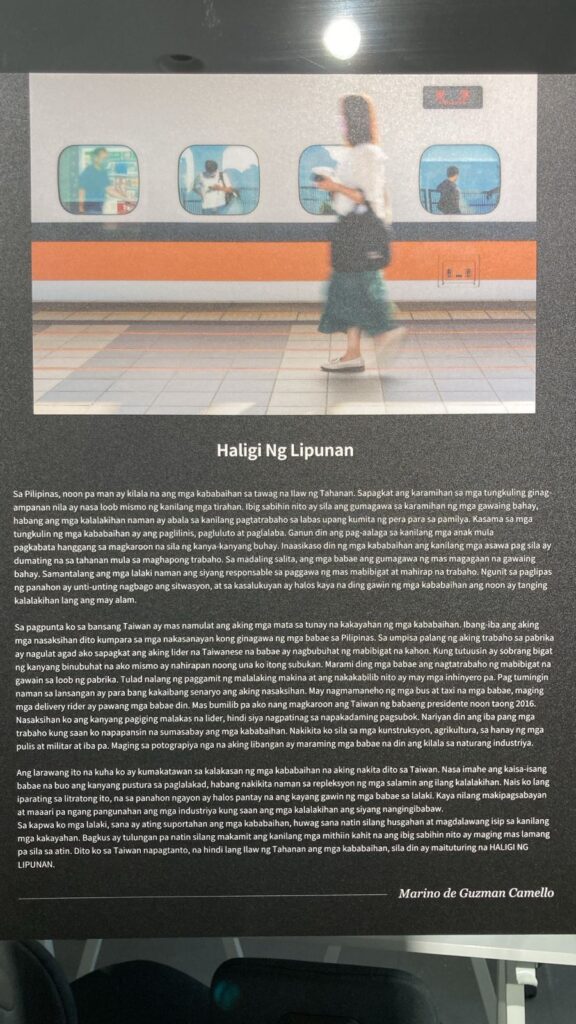

At the event, I had the chance to speak with some of the photographers. Marino, whose photo captured a woman walking past a train, explained that he wanted to highlight women’s strength by featuring four men in the train windows while placing the woman at the centre. His other photograph, of a blurry mannequin, symbolized his gratitude toward the fellow foreign workers who guided him when he first arrived in Taiwan, though he later realized that some influences, like drinking and infidelity, were less positive. His photo, titled Sino Ako? (“Who am I?”), reflects his journey of self-discovery and drawing boundaries.

And there was this Indonesian couple too. They had met at a worker agency back in Indonesia and married in Taiwan. The wife, a photographer, took a picture of their little boy, smiling in a sea of bubbles. Her employer had allowed her to keep her child in their household, and her husband, who worked in another town, could visit them on weekends.

There were many other images: workers playing by the beach on their day off, resting by fishing vessels, playing thumb wars with elderly Taiwanese, a spark flying off a helmet. Moments frozen in time.

The Ceremony

During the ceremony, the winners took the stage to receive certificates and prizes, followed by short speeches in their native languages, recorded live for family and friends on YouTube. Though I didn’t understand every speech, I could see the pride in their eyes. Some of them had their words written out on little scraps of paper, or on their phones. I could understand the speeches in Indonesian, of course. Thanking One-Forty, thanking their families, thanking other foreign workers. The hard work, the sacrifices, the love.

Each photographer received four postcards featuring their work. I saw some people swapping them, like a gift exchange. An Indonesian woman asked me to translate for her. She wanted to swap her postcard with a Filipino man’s because she admired his work.

Final Thoughts

Overall, I was deeply moved by the event. The language barriers seemed to disappear, thanks to the power of the images. I can’t wait to see the exhibition at the start of next year. Gotta bring tissues.

Discover more from Elhana S.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Yo, I was browsing and found km88bet. They’ve got a surprisingly good range of betting options – sports, casino games, the whole shebang! The odds seemed fair too. Maybe give it a go if you’re looking to place some bets. Check it out km88bet

Yo, gotta say, lucky96 ain’t bad! Been giving it a whirl and the odds seem pretty decent. The site’s easy to navigate, which is a huge plus in my book. If you’re feeling lucky, why not give lucky96 a shot?

Been playing on lucky96game for a while now. It’s pretty decent, I enjoy the variety of slots they offer. Had a couple of lucky streaks, hoping they continue. Here’s the link if you wanna try: lucky96game

Just spent some time on pkr666lucky, and I’m digging the design. Pretty clean and simple, no fuss. The ‘lucky’ part feels real! Definitely a place to try your hand at poker. Take a look pkr666lucky.

Heard some good things about Puntitcasino. Thinking of giving it a whirl. Anyone else play here? Let me know what you think of the slots and table games! Intrigued… puntitcasino

QQ188bet, eh? They got a solid selection of sports betting options. Been using them for a bit and haven’t had any major issues. Good place for a punt! Try QQ188bet! qq188bet

Just signed up with R7bet7. The sign-up bonus was pretty sweet. Will see how my luck holds out on the slots! Fingers crossed! r7bet7