The word linguistics is composed of two morphemes linguist and –ics. The base morpheme linguist derives from the Latin word lingua (“language” or “tongue”) whilst the suffix -ics tends to generate nouns that refer to fields of knowledge and practice. Does that explain anything about linguistics? No, anyone can google that. Does it sound ‘linguisticky’? Probably, especially if you trace back lingua to ,the Old Latin ,dingua, ,which has even been analysed down to its Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root.

But that’s not linguistics. That’s etymology (the study of the origins of words), and it’s only a minuscule aspect of the whole field. According to Cambridge dictionary:

Linguistics is the scientific study of the structure and development of language in general or of particular languages

Plus

…including the study of morphology, syntax, phonetics, and semantics. Specific branches of linguistics include sociolinguistics, dialectology, psycholinguistics, computational linguistics, historical-comparative linguistics, and applied linguistics.

Now that’s more like it.

What is “scientific” about linguistics?

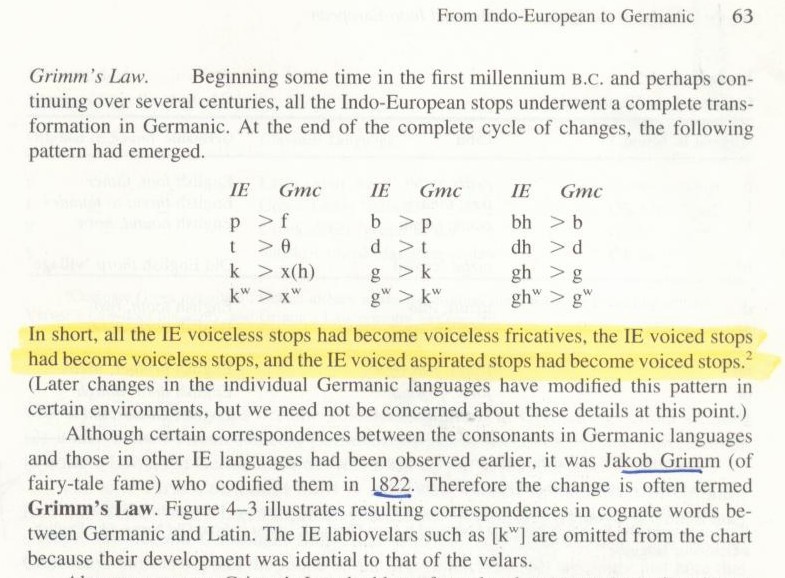

As Social Sciences subject, linguistics shares a scientific method not unlike any other subject within that field. It is generated through hypotheses and experimentations that prove or disprove the hypotheses. For instance, from the fact that the English word linguistics bears resemblance to the French linguistique, Italian linguistica, and Spanish lingüística, we can assume that they must come from the same root word. This leads to the gathering of data (experimentation) that leads to the formation of Proto-Indo-European, which is a hypothesis that has been tested enough to become commonplace in the linguistic practice, i.e. a theory. But this was mostly what linguists were concerned about in the 1800s. Back then, most linguists, called Neogrammarians, gathered writing scripts from generations past and compared how languages were written. This allowed them to hypothesise on language change and language relations. There were rules to this, as well. Take a look Grimm’s Law:

Millward, C.M.A Biography of the English Language,. Ft. Worth: Harcourt, 1996. Pg. 63

(Did you think that Brothers Grimm only wrote grim fairy tales? Nope, the oldest one, Jacob Grimm, actually came up with an important theory of systematic sound change, thus giving birth to historical phonology. The main takeaway is: ,you can be anything you want.,)

As you can see, the rules were made by studying ancient texts, picking out different spellings and comparing various Indo-European (IE) languages in written form. All to come out with this theory. And it’s tried and tested, accompanied by other Laws (e.g. Verner’s) to ensure that there are no exceptions to the rule. But linguistics has changed so much since the 1800s. Now people have accounts of spoken language and technology has allowed the study of languages to be even more systematic. Nowadays, with newfound technology, many researchers are more interested in the development of language itself, how language is acquired, how people perceive and process words (parsing), and basically what’s going in our brain while we’re ‘language-ing’. We can even argue that technology has facilitated the scientific-ness of linguistics.

Beyond its methodology, linguistics is scientific in its nature. It aims to discover more about the world, satisfying our knowledge and understanding. There are big questions surrounding language: How many languages are there in the world? Does humanity begin with one language? How do we express thought? The way linguistics attempts to solve these questions is by breaking them down to more specific questions. For example, how we express thought becomes a study of the human brain, which leads to a more affordable question: How does a brain injury affect language? Some linguists, such as Paul Broca and Carl Wernicke have studied patients with different types of agnosia to answer this question. The results produce an understanding that language is largely laterised on the left brain. This plausible conclusion answers part of the original question as to how we express our thought. The nature of linguistic study is to dissect a phenomenon to the tiniest nucleus, collecting reasonable data in the process, so that broader generalisation could be identified.

What is ‘language’?

Language is a vastly broad concept, so much so that as a first year undergraduate, I had to take three papers with two to five sub-fields underneath each, as follows:

- Modern Approaches to Language

- Semantics/Pragmatics

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics/Language variation

- Language Change

(This was in 2015. Oxford has probably revised the curriculum, like it has every year)

The way a university course studies language is almost as if language is an organism. That is because it is, in a way, very much alive. Language is fundamentally a means of communication, and communication is fundamental to humans. We are insiders of language. Hence, just as humans age with time and change with generation, so does language. Consequently, linguistics studies the properties of language, from then until now. The primary property of language is speech (or signs), an efficient and ephemeral form. Some branches of linguistics revolve around speech, such as phonetics, phonology, and discourse analysis. Some focus on writing, the secondary property of language, such as morphology, syntax, and semantics. All of them cover the structure of language. Other branches may analyse the functions of language; these entail applied linguistics, language acquisition, pragmatics, psycholinguistics, neurolinguistics, etc. The functions of language come under the umbrella of many disciplines, which broaden the scope of linguistics. Therefore, the object of study of linguistics is language, especially its structure, function, and relation to other disciplines.

Why did you study linguistics?

Ah, the age-old question. The short answer is: because I love learning languages. The long answer is: I hadn’t thought of my career options then.

Joking aside, I truly believe that it’s an enlightening subject, especially if you’re a multi-lingual language-enthusiast like me. Language is part of who we are. We use it think, to communicate, to reflect as well as to express. Linguistics is the scientific study of language, but it is also the scientific study of humans. Just like how psychology reveals about humanity through the study of human mind, linguistics reveals about humanity through the study of human language. (Although it is true that linguistics also involves the study of animal language, we use it to compare to our manner of speaking). As Noam Chomsky said, “Language is a mirror of mind in a deep and significant sense.” That connotes that language reflects the way we think. It follows that the way we think is layered in complex relationship between the signifier and the signified. Human thought is uniquely diverse and marvellous as a whole. It is innovative and ever-changing. That is why we study language: to explore the depth and creativity of human mind through its expression. The object of linguistics is language, but the aim of linguistics is the discovery of human mind.

TL;DR

Linguistics is about Language (a mental capacity) and languages (why apps like Duolingo exists). And yeah it’s quite scientific.

References

A. Akmajian, R. A. Demers, A. K. Farmer and R. M. Harnishn (2010), Linguistics (6ed.). MIT.

N. Chomsky (1975), Reflection on Languages. New York: Pantheon Books.

V. Fromkin and R. Rodman (2011), An Introduction to Language. Canada: Nelson Education, Ltd.

Discover more from Elhana S.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Yo! Kkkjilibet’s got some interesting stuff going on. Checking it out and finding some decent games. Worth a shot if you’re looking for something different. Give it a whirl! kkkjilibet

Hey peeps, ijogos1 is a decent spot for some quick games. Nothing too fancy, but it gets the job done when you’re bored. Worth a look-see ijogos1.

Yo, check out goldenhoyeah1. I’ve been playing it for a while, and it’s pretty good stuff. Nice graphics and fun gameplay too goldenhoyeah1.

Tried my luck at gbgbet444 today. Feeling pretty good about it. Give it a look see, might be your lucky day too! gbgbet444

Trying to get into FB777? The apps login here is legit and smooth sailing fb777applogin.

Alright, winph.555, let’s see what you got! Heard some whispers, gotta try it out myself. Hope it lives up to the hype! winph.555

Dude, wanna watch live matches? Matbet canlı maç izle is where it’s at. No buffering, just pure football heaven. Check it: matbet canlı maç izle